![]() Since the seminal research of Herbert Möller in the late 1960s and Jack Goldstone in the early 1990s, numerous political researchers have called attention to the tendency of countries with youthful populations—often called a “youth bulge”—to be more vulnerable to civil conflict than nearby states with a more mature population. Then a 2016 article upset political demography’s apple cart. When investigating countries with at least three consecutive years without an intra-state conflict, Omar Yair and Dan Miodownik found a fundamental difference between ethnic and non-ethnic warfare. The risk of a non-ethnic conflict was, indeed, higher under youth-bulge conditions. However, they found that youth bulges (measured at the country level, rather than at the ethnic level) were unrelated to the risk of an onset of an ethnic conflict.

Since the seminal research of Herbert Möller in the late 1960s and Jack Goldstone in the early 1990s, numerous political researchers have called attention to the tendency of countries with youthful populations—often called a “youth bulge”—to be more vulnerable to civil conflict than nearby states with a more mature population. Then a 2016 article upset political demography’s apple cart. When investigating countries with at least three consecutive years without an intra-state conflict, Omar Yair and Dan Miodownik found a fundamental difference between ethnic and non-ethnic warfare. The risk of a non-ethnic conflict was, indeed, higher under youth-bulge conditions. However, they found that youth bulges (measured at the country level, rather than at the ethnic level) were unrelated to the risk of an onset of an ethnic conflict.

La Différence Vit?

In research for a soon-to-be-published article, I set out to investigate a bit beyond Yair and Miodownik’s conclusions, asking two new questions:

- Do the differences that Yair and Miodownik observed extend to countries with a history of recent of conflict?

- How do these effects play out over the course of the age-structural transition—as populations age, shifting from a youthful population with a low median age, to a more mature population with a high median age?

For the rest of the article on New Security Beat … CLICK HERE. Or download briefing: “Revolutions Just Age Away” in .pdf.

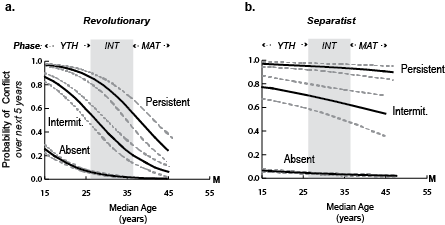

Fig. 1. The patterns of 5-year risk of (a.) revolutionary conflict and (b.) separatist conflict over the length of the age-structural transition. While the three types of conflict-history cases of revolutionary conflict (absent, intermittent, persistent) all respond to aging, the same classes of separatist conflict appear much less responsive.

Fig. 1. The patterns of 5-year risk of (a.) revolutionary conflict and (b.) separatist conflict over the length of the age-structural transition. While the three types of conflict-history cases of revolutionary conflict (absent, intermittent, persistent) all respond to aging, the same classes of separatist conflict appear much less responsive.

Conflict history classes: Absent: without conflict during the prior four years; Intermittent: 1 or 2 years of conflict during the prior 4 years; Persistent: 3 or 4 conflict years during the prior 4 years.