What is an Age-structural Function?

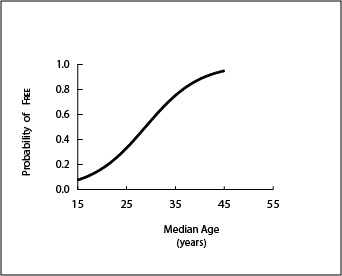

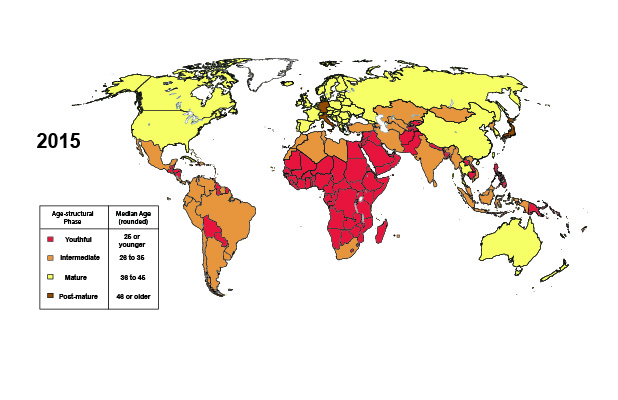

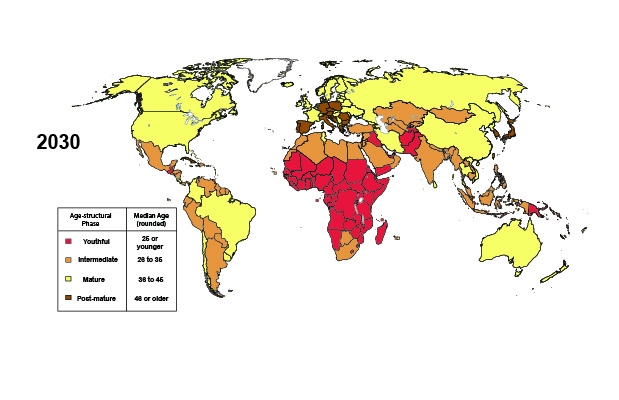

An age-structural function is a two-dimensional graphic form of an age-structural model. This function describes a range (Y-axis) of probabilities of being within a category at all points (median ages) across the age-structural domain (the X-axis of the graph). To neatly capture nearly all recent positions in the age-structural transition, now and in the foreseeable future, the standard form of this graph extends over a domain that begins at a median age of 15 years and ends at 55 years. This standardized form is not perfect. Over the course of UN Population Division (UNPD) estimates (1950 to 2015), the populations of a few states (including Niger in 2015) have experienced median ages below 15.0 years. On the high side of the domain, however, no country-level age structure has yet gone beyond a median age of 48. Nonetheless, the UN Population Division projects that Japan will reach a median age higher than 50 years before 2030, and that several European and additional East Asian countries will follow it into the post-mature phase (a median age of 45.6 or higher) soon thereafter.

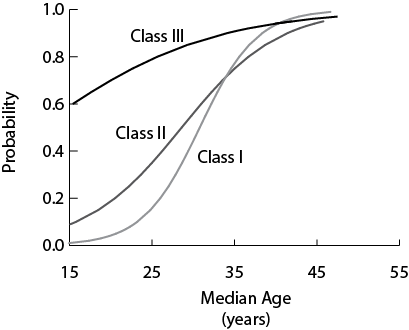

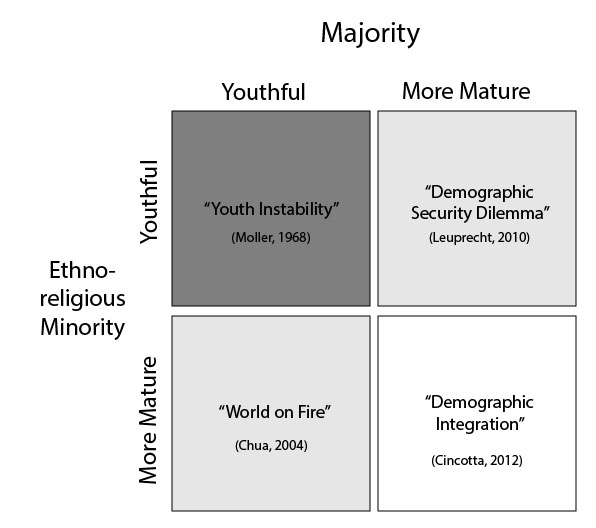

Not all age-structural functions that are fit to data by an age-structural model are qualitatively similar. Age-structural functions have been categorized into three qualitative classes (I, II, III), according to the conditions associated with the age-structural function that they describe (Fig. 1). These conditions influence the form and fit of the age-structural function.[i]

These three classes suggest differences in the strength of the relationship’s directionality and punctuality. Functional directionality can also be expressed as the ratio between the frequency at which it advances into a category, relative to the frequency at which it retreats back into this category. Class I age-structural functions (such as income and education functions) express high ratios of directionality and feedback between the indicator and movement along the age structural transition (or fertility decline). Class III functions (such as the frequency of intra-state conflict or the initiation of intra-state conflict) typically express low ratios. Class II functions (such as being assessed as Free in Freedom House’s annual survey) are like class I functions, but not as directional. States backslide more often, and there may be very little feedback, if any, associated with the relationship. Functional punctuality measures the tendency for advancement to be associated with a particular median age. This quality can be measured by the steepness of the curve (i.e., value of first derivative) at its inflection point (where p=0.50). Class I age-structural functions are most punctual; class III, the least.

Figure 1. Three classes of age-structural function (I, II, III). Each is associated with a particular set of dynamics exhibited by states, in terms of a categorical dependent variable (Y), over the length of the age-structural domain (X axis).

[i] Cincotta, R. 2017. “The Age-structural Theory of State Behavior.” in Oxford Reference Encyclopedia: Empirical International Relations Theory, edited by W. Thompson. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Download here.

Read about

Read about

Read “

Read “ r of children that women are bearing over their reproductive lifetime). The second most influential factor has been increasing longevity. Not all trends associated with modernization, however, contribute to aging. Declines in childhood mortality have served to slow aging’s pace or make it retreat, as have waves of youthful immigrants (until the immigrants themselves age) and occasio

r of children that women are bearing over their reproductive lifetime). The second most influential factor has been increasing longevity. Not all trends associated with modernization, however, contribute to aging. Declines in childhood mortality have served to slow aging’s pace or make it retreat, as have waves of youthful immigrants (until the immigrants themselves age) and occasio ong “saver” societies).

ong “saver” societies).

Read “

Read “