Youthful Clusters

Have you ever noticed that shifts in the world political order are clustered in time and geographical location? For example, the late-1980s and 1990s, economists and political scientists were caught off guard by the economic rise and a series of political reforms among the East Asian Tigers (South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Singapore, and Indonesia), quickly setting them apart from the rest of the developing world. The Tigers’ successes were followed in the early 2000s by an unheralded burst of liberal democracy among Caribbean and Latin American states (including Brazil, Chile, Argentina, Guyana, Trinidad & Tobago). Then, beginning in 2010, came the Arab Spring, during which Tunisia’s attainment of liberal democracy caught regional political experts completely off guard.

Have you ever noticed that shifts in the world political order are clustered in time and geographical location? For example, the late-1980s and 1990s, economists and political scientists were caught off guard by the economic rise and a series of political reforms among the East Asian Tigers (South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Singapore, and Indonesia), quickly setting them apart from the rest of the developing world. The Tigers’ successes were followed in the early 2000s by an unheralded burst of liberal democracy among Caribbean and Latin American states (including Brazil, Chile, Argentina, Guyana, Trinidad & Tobago). Then, beginning in 2010, came the Arab Spring, during which Tunisia’s attainment of liberal democracy caught regional political experts completely off guard.

However, demographers were less surprised (see 2008/09 article predicting the rise of a democracy in North Africa). The states of these regions were entering the demographic window–a period during the age-structural transition when states typically progress economically and often undergo political changes.

Similar temporal and geographical clustering arises where progress in the age-structural transition has not occurred; i.e., among youthful clusters of states that are “stuck in age-structural time.” Today, the vast majority of revolutionary conflicts (insurgencies that are focused on overthrowing the political system or altering the central government, as indicated in the latest (2017) version of the UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Data Set) occur in youthful states—those with a median age at or below 25.5 years. Youthful states typically appear in clusters, and these conflicts tend to spread across their borders, typically stopping at the borders of non-youthful states.

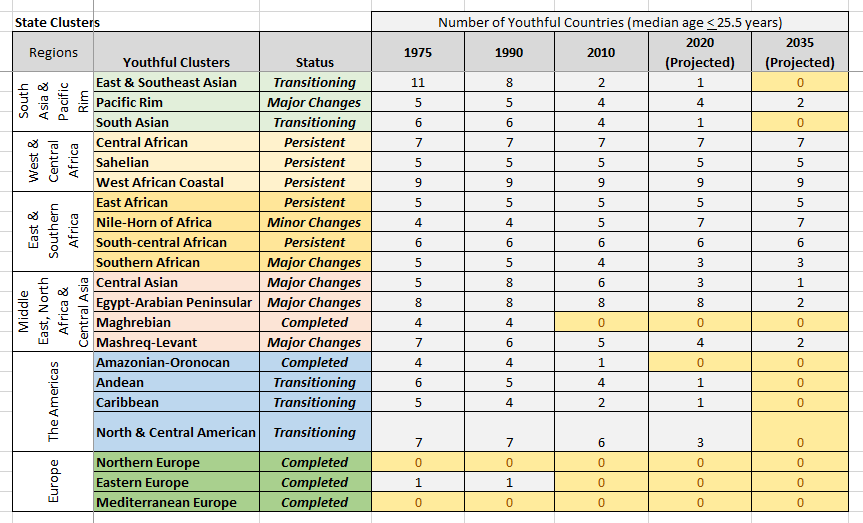

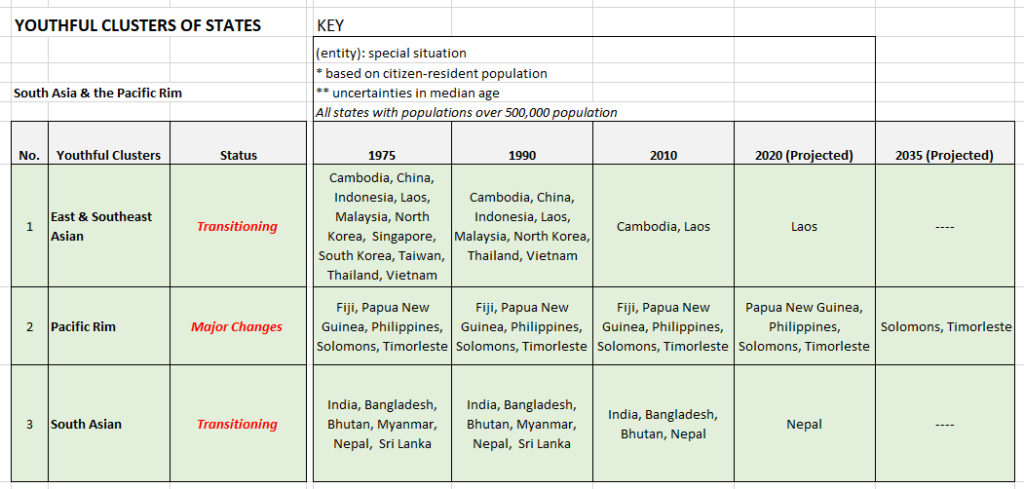

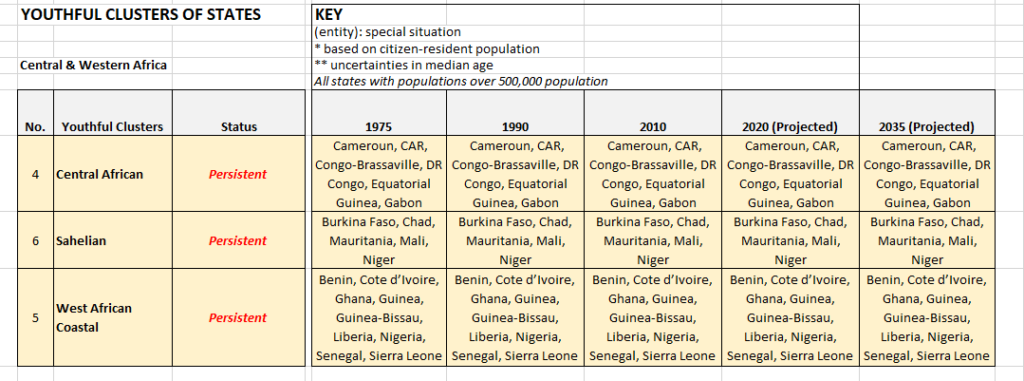

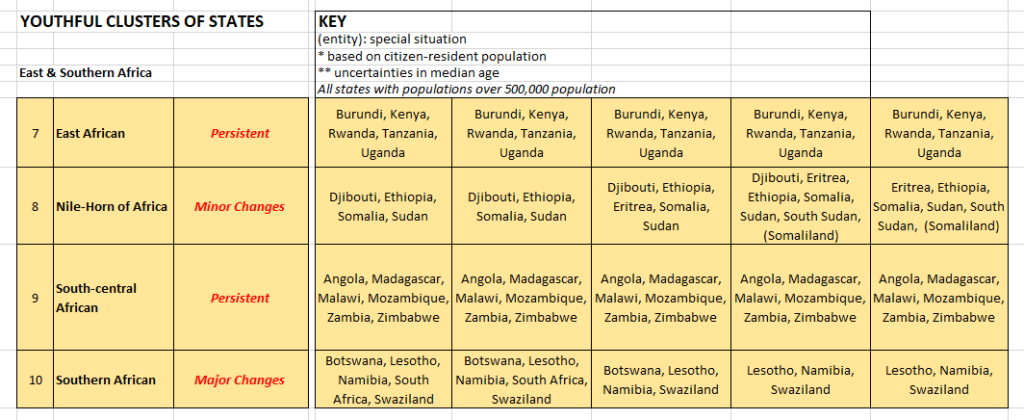

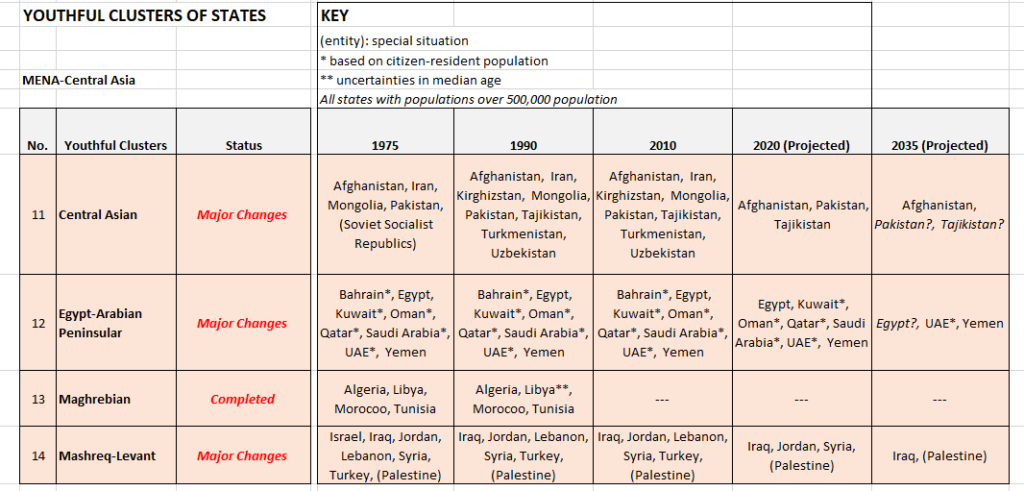

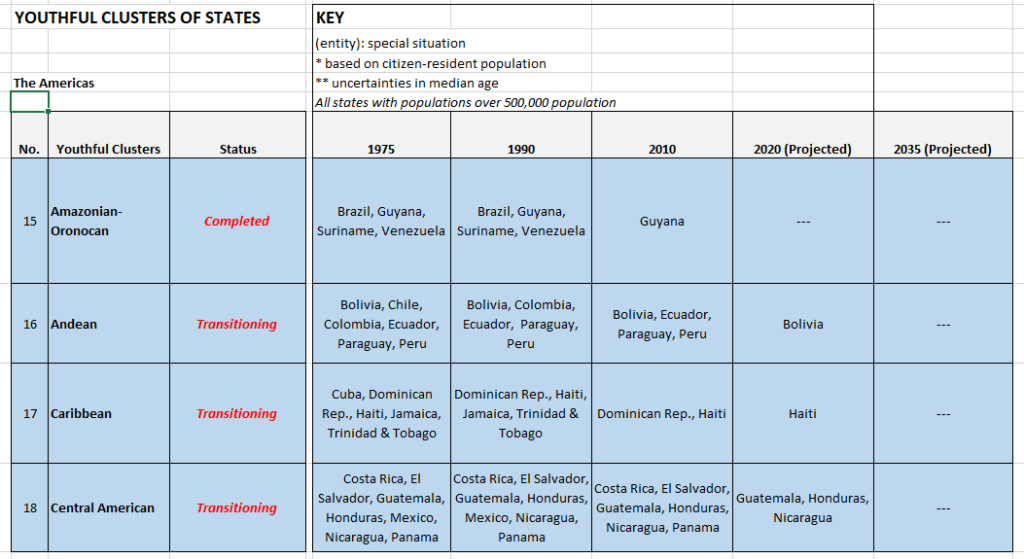

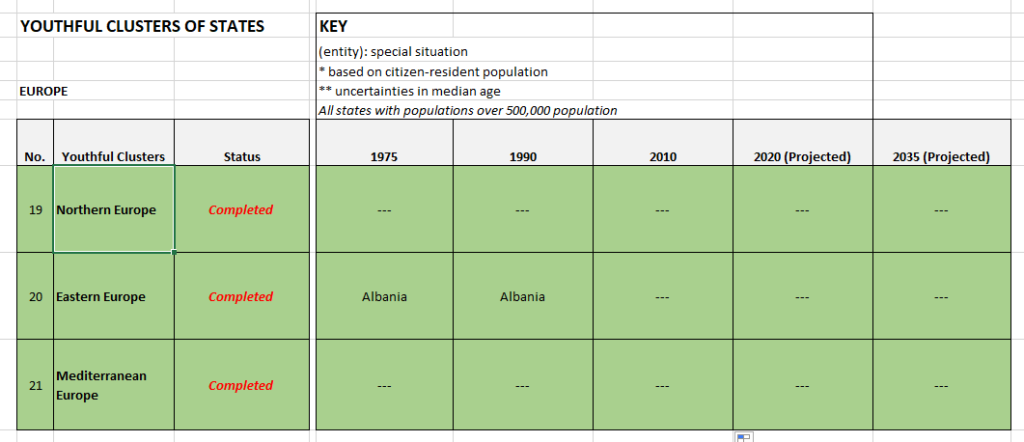

In the following 6 regional tables (South Asia & the Pacific Rim; West & Central Africa; East & Southern Africa; the Middle East, North Africa & Central Asia; the Americas; and Europe), I’ve divided the world into 21 clusters of states. In 1975, 18 of those clusters were dominated by youthful states–countries with a median age of 25.5 years or less.

A lot has transpired since then. I track the cluster to 1990, and 2020 (a very short-term projection), and finally a projection to 2035 (using the UN Population Division’s medium fertility variant). As the years progress, states experiencing fertility decline advance to the next phase of the age-structural transition (the intermediate phase, between a median age of 25.6 and 35.5 years). These drop out of the cluster until, as in 3 cases, the youthful cluster disappears (see Table 1, below).

However, 16 clusters still remain. Four situated along the midriff of Africa (West Africa Coastal Cluster, the Sahelian Cluster, Central African Cluster, and South Central African Cluster), within the tropics, persist just as they did over 40 years ago. These are Western and Central African clusters likely to be significant sources of revolutionary conflict and other forms of political instability throughout the rest of the century. Another 7 clusters (in the Middle East, other parts of Asia, and Africa) have gone through minor and major changes also generate ongoing as well as future risks. However, according to the UN Population Division’s demographic projections, these may gradually fade over the coming three decades.

The final 5 clusters of states are “in transition.” The states in these groups are experiencing fertility decline and shifting to the intermediate phase of that age-structural transition. These youthful clusters may disappear over the coming two decades.