Minority Youth Bulges and State Stability

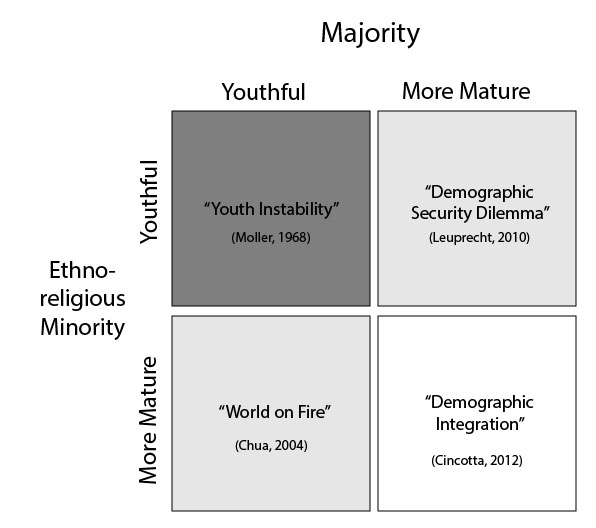

Read about Ethnodemographic Differences and majority-minority relations (first posted in The New Security Beat, 2012). Since its appearance, this two-by-two model of sub-state demographic differences has been increasingly used as a means of spotting escalating ethnic tensions and warning of future armed conflicts.

Read about Ethnodemographic Differences and majority-minority relations (first posted in The New Security Beat, 2012). Since its appearance, this two-by-two model of sub-state demographic differences has been increasingly used as a means of spotting escalating ethnic tensions and warning of future armed conflicts.

Read an application of the model (Barnhart et al., 2015, “The Refugee Crisis in the Levant”); and others by Rachel Blomquist on Myanmar’s Rohingya conflict (Fall, 2016; Spring, 2016).

Figure 1. Two-by-two sub-state model of majority-minority relations, based on the age structural configurations of the majority and a politically organized minority population. Where there is no external interference, the “demographic integration” condition is hypothesized to be the most politically stable.

See the New Security Beat essay by Rachel Blomquist and Richard Cincotta on

See the New Security Beat essay by Rachel Blomquist and Richard Cincotta on  View “

View “ Read “

Read “