[Among the top 5 New Security Beat Posts, December 2019]

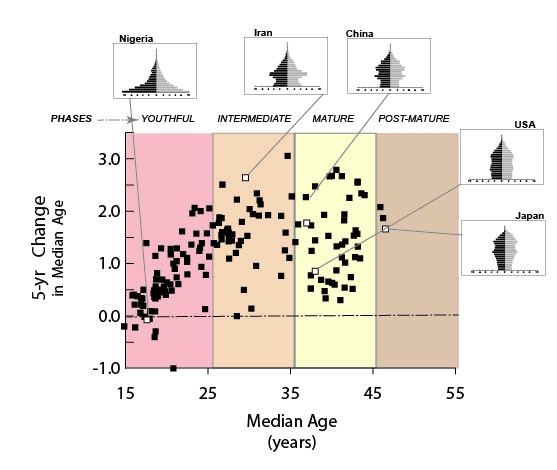

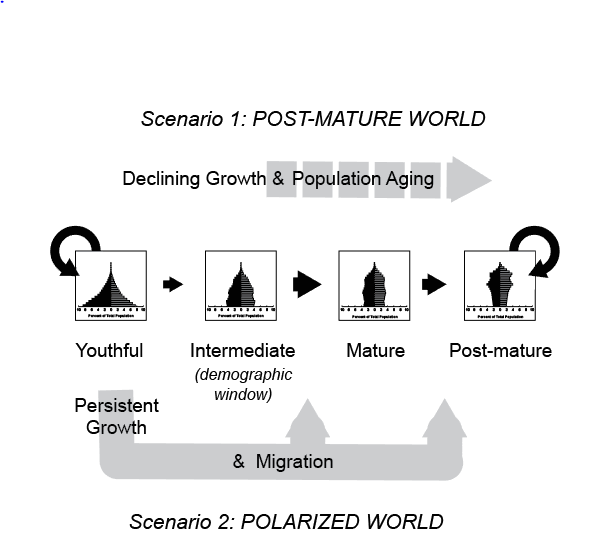

Demography’s theoretical end-state is a set of hard-to-escape conditions typified by low and often sub-replacement levels of fertility, large proportions of retirees, and an aging workforce—an endpoint that the National Intelligence Council’s Global Trends reports refer to as post-maturity. The shift toward post-maturity is so unrelenting in parts of Europe and East Asia that some analysts imagine humanity plunging globally into post-maturity. However, this scenario, which I call “Post-mature World,” is looking much less likely than its non-endpoint alternative (see Figure 1), a chronically demographically “Polarized World.”

To visit the complete essay on the New Security Beat website, click HERE. Or, download the essay HERE.

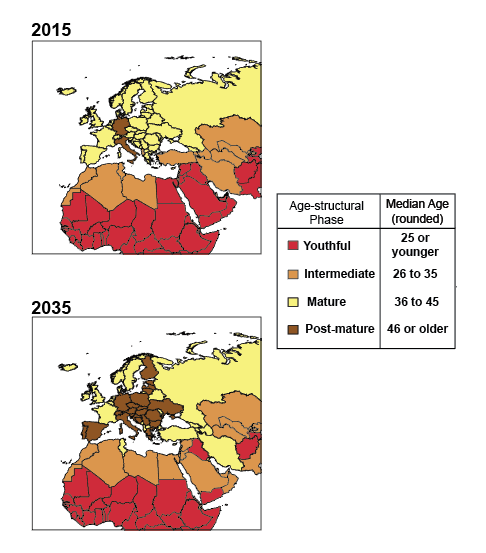

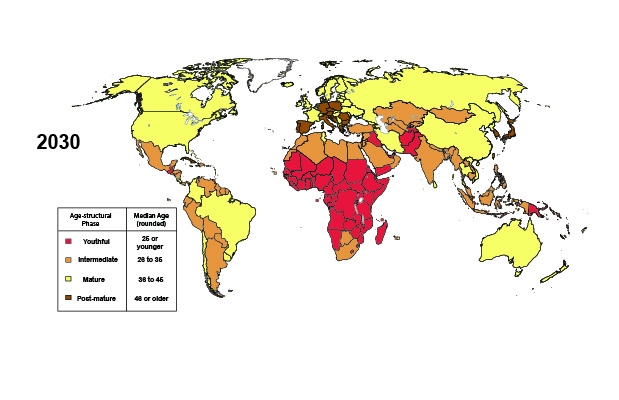

Maps. The age-structural phases of countries in Europe and in parts of Africa and Asia, 2015 & 2035 (projected). Maps represent the UN Population Division’s current estimates of median ages for 2015 and projections for 2035 (UN medium fertility variant). By 2035, most of Europe’s states will likely have advanced into post-maturity, whereas in the Sahel and tropics of Africa, countries will probably still be in the youthful phase of the age-structural transition.

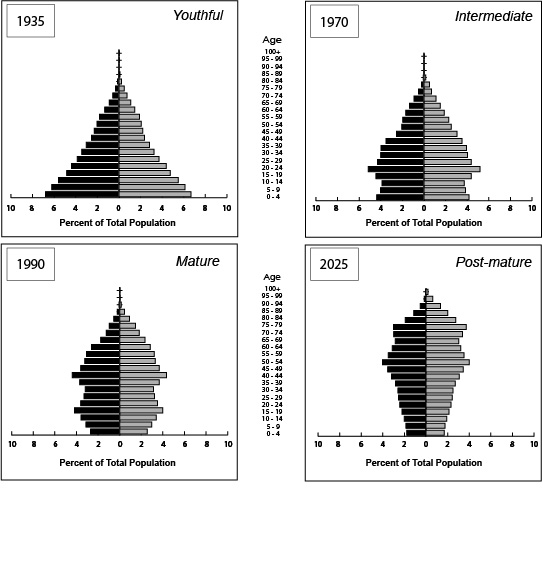

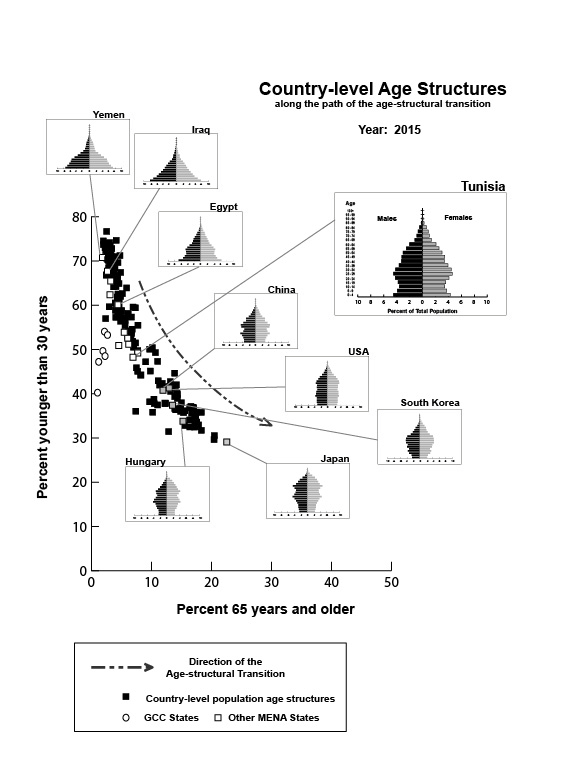

Figure 1. Post-mature World and its alternative Polarized World, showing the Global Trends four-phase schema representing the path of the age-structural transition. Black arrows indicate the transition’s path and identify the two hard-to-escape demographic conditions, the youthful and post-mature phases. In a Post-mature World, countries age and their populations eventually decline. In a Polarized World, human population continues to grow in the youthful regions, stimulating increased migration to nearby states and to more mature regions.

Read “

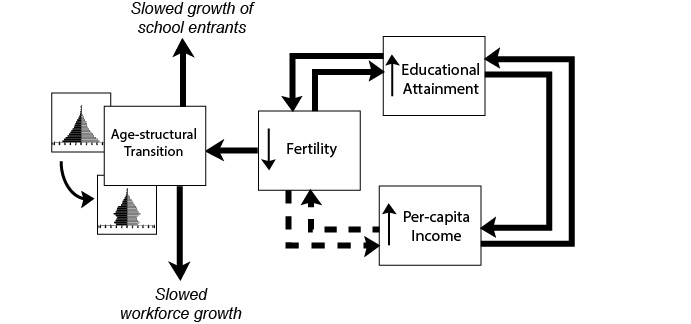

Read “ r of children that women are bearing over their reproductive lifetime). The second most influential factor has been increasing longevity. Not all trends associated with modernization, however, contribute to aging. Declines in childhood mortality have served to slow aging’s pace or make it retreat, as have waves of youthful immigrants (until the immigrants themselves age) and occasio

r of children that women are bearing over their reproductive lifetime). The second most influential factor has been increasing longevity. Not all trends associated with modernization, however, contribute to aging. Declines in childhood mortality have served to slow aging’s pace or make it retreat, as have waves of youthful immigrants (until the immigrants themselves age) and occasio ong “saver” societies).

ong “saver” societies).