by Richard Cincotta

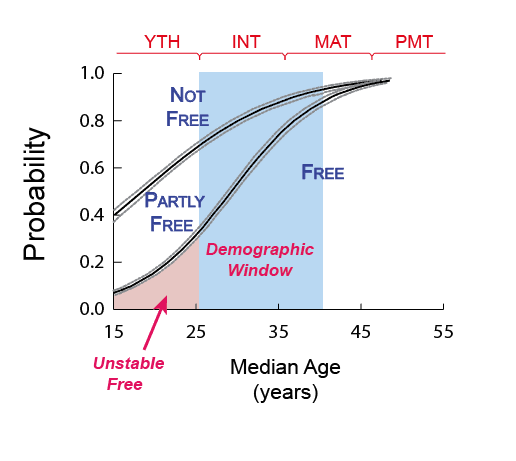

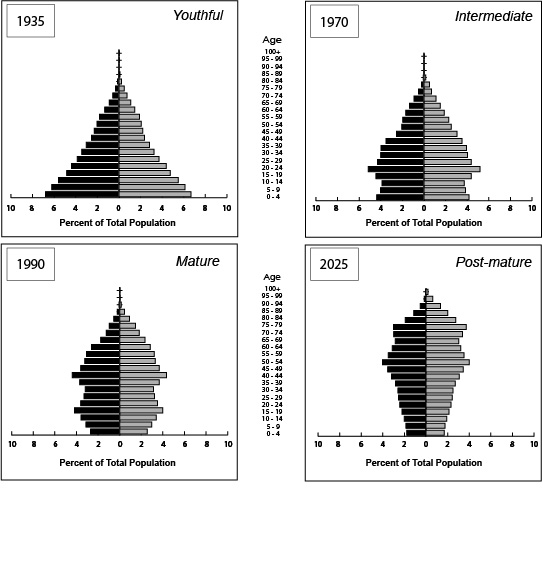

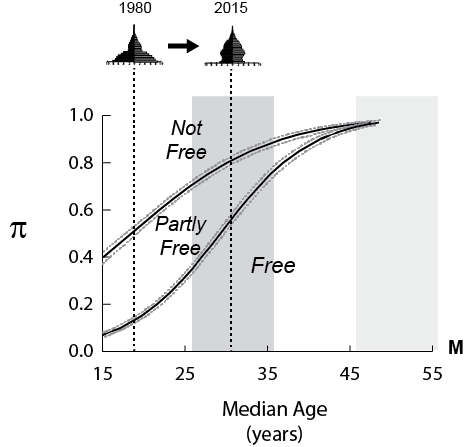

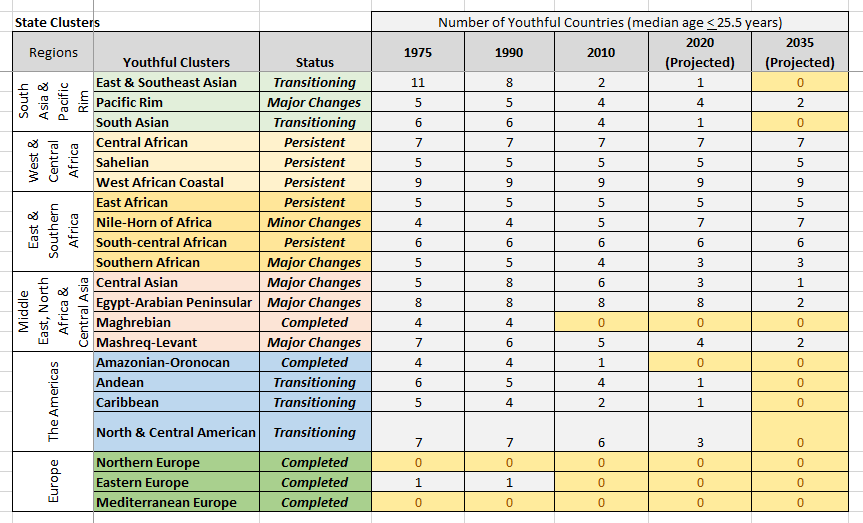

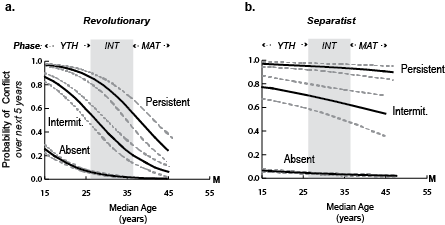

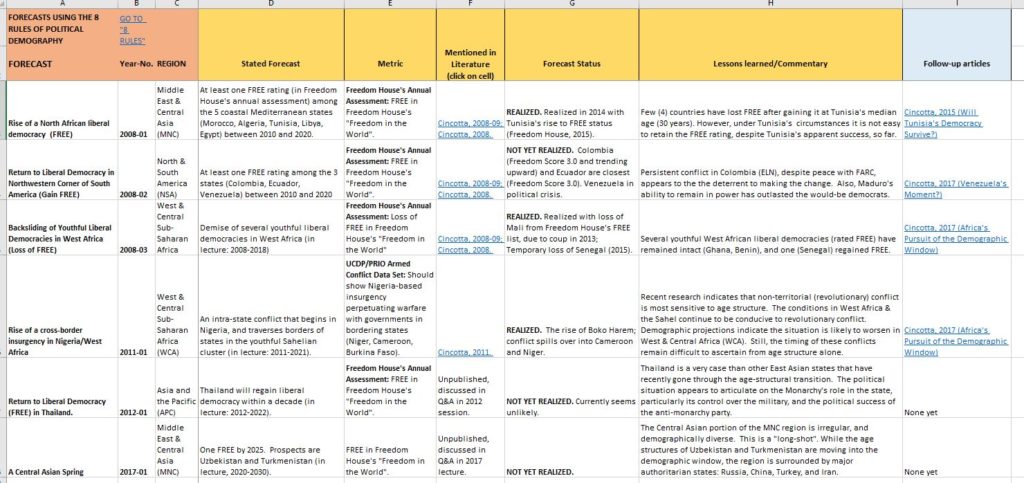

In 2007, at the (U.S.) National Intelligence Council, a colleague and I set out to determine if we could forecast two distinct political phenomena, the rise and the demise of high levels of democracy. To guide our decade-long forecasts, we relied on a simple statistical model and a spreadsheet of demographic projections from the UN’s 2006 World Population Prospects data set. Now that the experimental period (from 2010 to 2020) has ended, we can look back and ask: How well did these forecasts perform?

Overall, surprisingly well; but by no means, flawlessly. In fact, we expected too much political liberalization during a decade when democracy was largely in retreat. Yet, had our age-structural forecasts been taken more seriously when first presented and published (see “Half a Chance”, published by the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program), foreign affairs analysts might have been amply forewarned of two of the decade’s most unanticipated political events: Tunisia’s rise to liberal democracy (Free in Freedom House’s annual assessments); and the demise of four of West Africa’s liberal democracies (decline from Free to Partly Free or Not Free).

To continue reading, go to: New Security Beat, Predicting the Rise and Demise of Liberal Democracy: How well did we do?