Iran in Transition: The Implications of the Islamic Republic’s Changing Demographics

Richard Cincotta & Karim Sadjadpour

December 2017, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

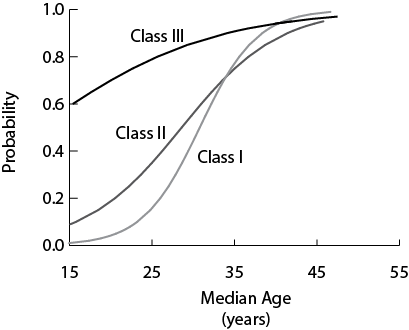

In the late 1980s, Iran’s revolutionary government deployed a series of contraceptive and counseling services that would become one of the world’s most effective voluntary family planning programs. The country’s total fertility rate—the average number of children an Iranian woman could expect to bear during her lifetime—fell from five and a half at the program’s inception to two children per woman about two decades later. Consequently, Iran has entered an economically advantageous demographic window of opportunity, during which its working-age, taxable population far outnumbers children and elderly dependents. This transition has important implications for the country’s economic and political trajectory, as well as for U.S. policy toward Iran. [read more of the summary]

Go to the online version of Iran in Transition.

Download: Iran in Transition.