“Emulating Botswana’s Approach to Reproductive Health Services Could Speed Development in the Sahel”

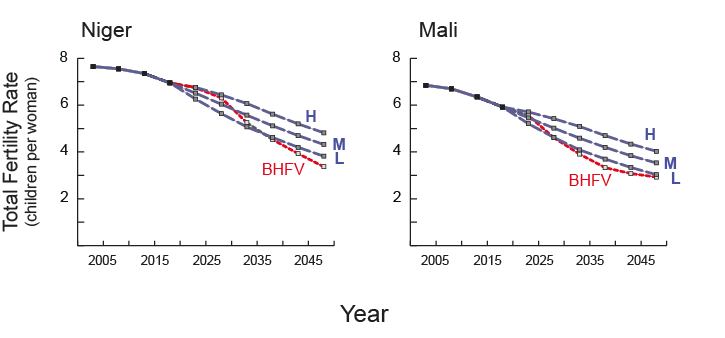

This new web essay (on the NSB website <click here>) reviews research that uses the relatively rapid changes in Botswana’s age-specific fertility rates to produce a “Botswana historic fertility variant” and applies this projection to the populations of countries in the Western Sahel—a contiguous cluster of states with populations that remain at the early stages of the fertility transition. For these high-fertility countries, projections of this variant (up to the year 2050) fall roughly around the TFR trajectory the UN low fertility variant.

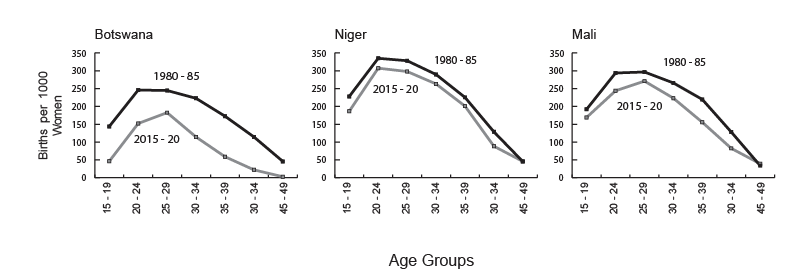

Figure. Declines in Fertility Across Women’s Age Groups in Botswana, Niger, and Mali from 1980–85 to 2015–20. In Botswana, girls’ education and a quality family planning program helped adolescents postpone childbearing and helped older women avoid the risks associated with unwanted middle-age pregnancy (Data source: UN Pop. Div., 2019 Rev.)

This exercise provides a glimpse of what could possibly be achieved in some states in tropical Africa by emulating Botswana’s efforts to ramp up access to family planning, to decrease the frequency of teen pregnancies, and to increase girls’ educational attainment. However, the essay notes how different the Sahelian countries are from Botswana—a well-governed, resource-endowed southern African country with a relatively small, urbanized (>65%) population (2.3 million)—and thus the formidable challenges those differences present in attempting to replicate the pace of Botswana’s fertility transition.

Figure. UN Population Division’s High, Medium, and Low Fertility Variants for Niger and Mali vs. Botswana Historical Fertility Variant (BHFV). In both cases, applying Botswana’s age-specific pattern of fertility declines would produce a projection roughly similar to the current UN low fertility variant. (Data Source: UN Pop. Div., 2019 Rev. & author’s research)

For the full essay, go to the NSB website <click here>

Or, download the essay <click here to download>

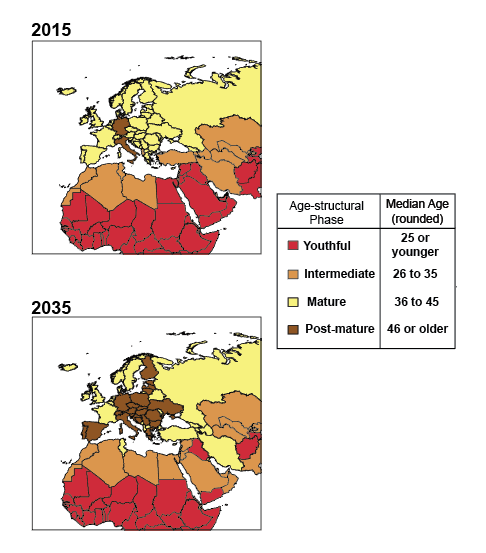

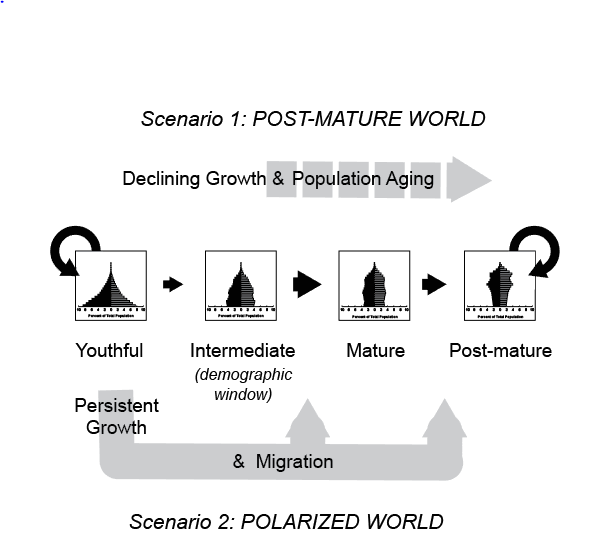

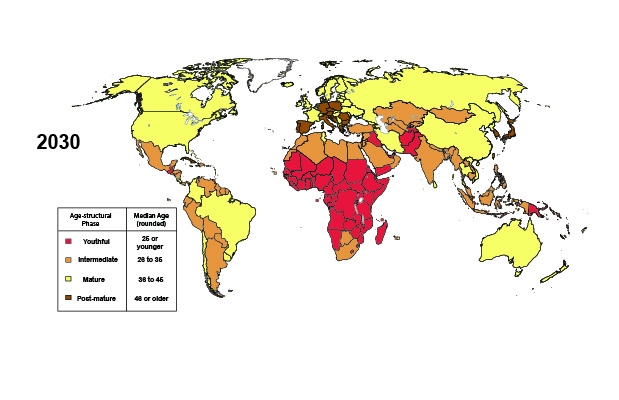

Over the past 25 years, economic and political demographers have focused on documenting the improvements in state capacity and political stability that have been realized in the wake of fertility declines in much of East Asia, Latin America, and most recently in the Maghreb of North Africa (Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria). Nonetheless, foreign affairs, defense and intelligence analysts still seem confused over when and where this demographic dividend should occur—and whether the youthful, low-income states of Sub-Saharan Africa are due to experience the dividend’s economically favorable age structures anytime soon. Because two very different development narratives vie for these analysts’ attention, their confusion is not that surprising.

Over the past 25 years, economic and political demographers have focused on documenting the improvements in state capacity and political stability that have been realized in the wake of fertility declines in much of East Asia, Latin America, and most recently in the Maghreb of North Africa (Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria). Nonetheless, foreign affairs, defense and intelligence analysts still seem confused over when and where this demographic dividend should occur—and whether the youthful, low-income states of Sub-Saharan Africa are due to experience the dividend’s economically favorable age structures anytime soon. Because two very different development narratives vie for these analysts’ attention, their confusion is not that surprising. Read “

Read “ Read “

Read “