View “Government without the Ultra-Orthodox?: Demography and the Future of Israeli Politics” by Richard Cincotta, published in the Foreign Policy Research Institute’s E-Notes, December 2013.

View “Government without the Ultra-Orthodox?: Demography and the Future of Israeli Politics” by Richard Cincotta, published in the Foreign Policy Research Institute’s E-Notes, December 2013.

It would be hard to conjure up a more grave and immediate set of peacetime challenges than those that Israel faces—from the advances in Iran’s nuclear program, to the political instabilities that continue to play out along the length of its borders. Yet, the outcome of the January 2013 election of the 19th Knesset appears to have been shaped less by the Israeli public’s perceptions of foreign threats, and more by its domestic concerns.

This brief note raises two questions: How did Yesh Atid rise from a virtual standing start to claim a critical position in Israel’s 33rd government? And what does this party’s electoral achievement mean for the future of Israel’s democracy?

Download “Government Without the Ultra-Orthodox?” here …

Read “

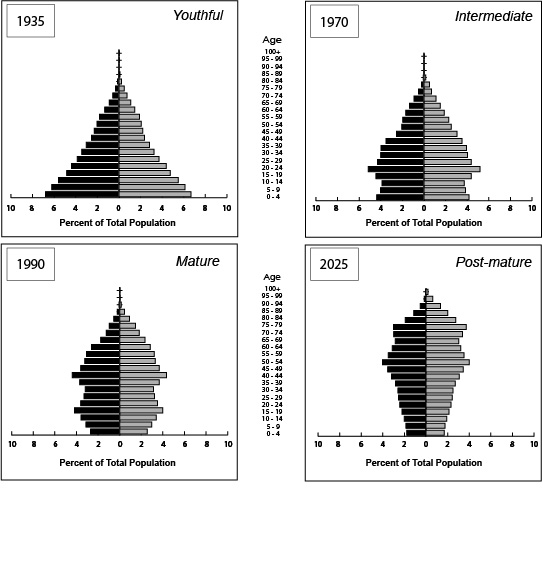

Read “ r of children that women are bearing over their reproductive lifetime). The second most influential factor has been increasing longevity. Not all trends associated with modernization, however, contribute to aging. Declines in childhood mortality have served to slow aging’s pace or make it retreat, as have waves of youthful immigrants (until the immigrants themselves age) and occasio

r of children that women are bearing over their reproductive lifetime). The second most influential factor has been increasing longevity. Not all trends associated with modernization, however, contribute to aging. Declines in childhood mortality have served to slow aging’s pace or make it retreat, as have waves of youthful immigrants (until the immigrants themselves age) and occasio ong “saver” societies).

ong “saver” societies).

Read “

Read “ Read “

Read “