Read “Minority Youth Bulges and the Future of Intrastate Conflict,” by Richard Cincotta, posted in the New Security Beat on October 13, 2011. The sub-state demographic theory of the risk of ethnoreligious conflict described in this essay has been applied to several countries. See “The Refugee Crisis in the Levant” (Barnhart et al., 2015, American U.), and The Demography of the Rohingya Conflict (Blomquist & Cincotta, 2015), and the Ethno-demographic Dyanmics of the Rohingya Conflict.

Read “Minority Youth Bulges and the Future of Intrastate Conflict,” by Richard Cincotta, posted in the New Security Beat on October 13, 2011. The sub-state demographic theory of the risk of ethnoreligious conflict described in this essay has been applied to several countries. See “The Refugee Crisis in the Levant” (Barnhart et al., 2015, American U.), and The Demography of the Rohingya Conflict (Blomquist & Cincotta, 2015), and the Ethno-demographic Dyanmics of the Rohingya Conflict.

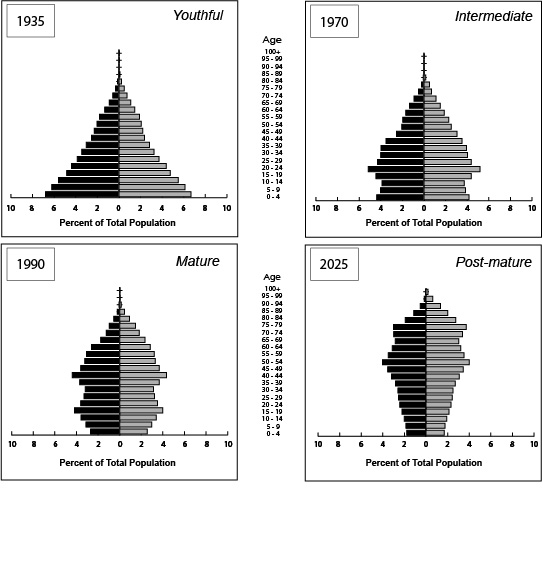

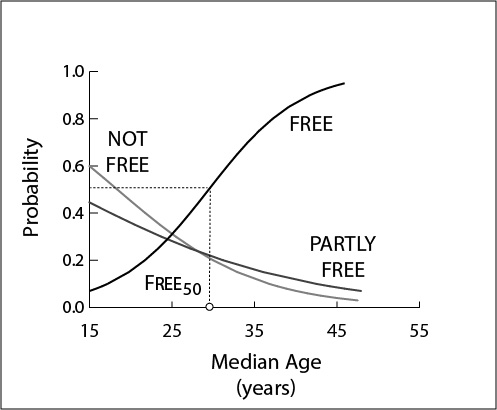

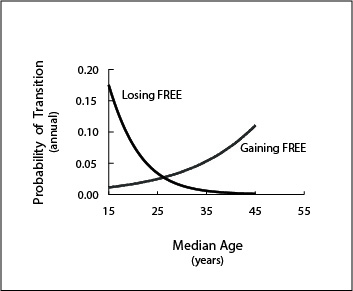

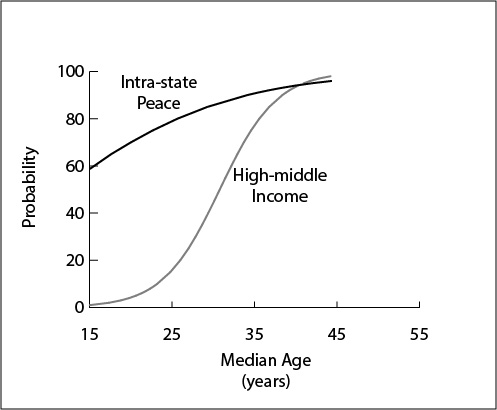

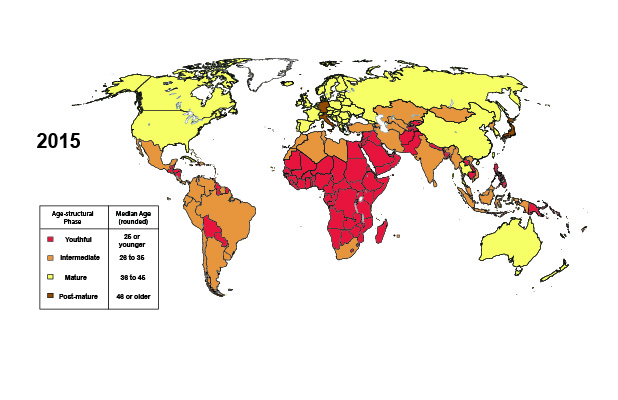

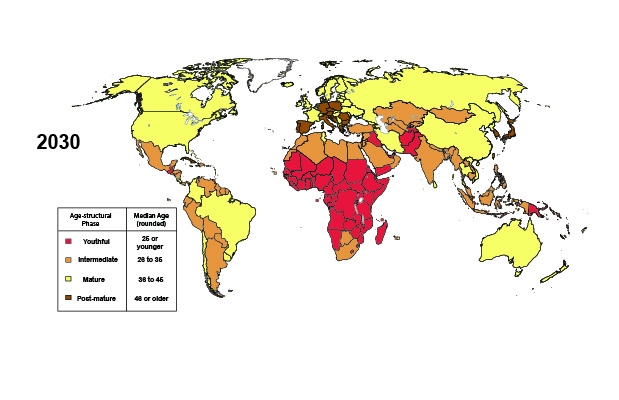

From a demographic perspective, the global distribution of intrastate conflicts is not what it used to be. During the latter half of the 20th century, the states with the most youthful populations (median age of 25.0 years or less) were consistently the most at risk of being engaged in civil or ethnoreligious conflict (circumstances where either ethnic or religious factors, or both, come into play). However, this tight relationship has loosened over the past decade, with the propensity of conflict rising significantly for countries with intermediate age structures (median age 25.1 to 35.0 years) and actually dipping for those with youthful age structures (see Figure 1 below).

Why has this relationship changed? At least two underlying trends help explain the shift:

- Over the last two decades, the deployment of peace support operations to countries with youthful populations has surged (described in a previous post on New Security Beat); and

- Ethnoreligious conflicts have gradually, though noticeably, increased among a group of states with a median age greater than 25.0 years (including Thailand, Turkey, and Russia).

ong “saver” societies).

ong “saver” societies).