Age-structural Theory’s Overt Focus on Predictions

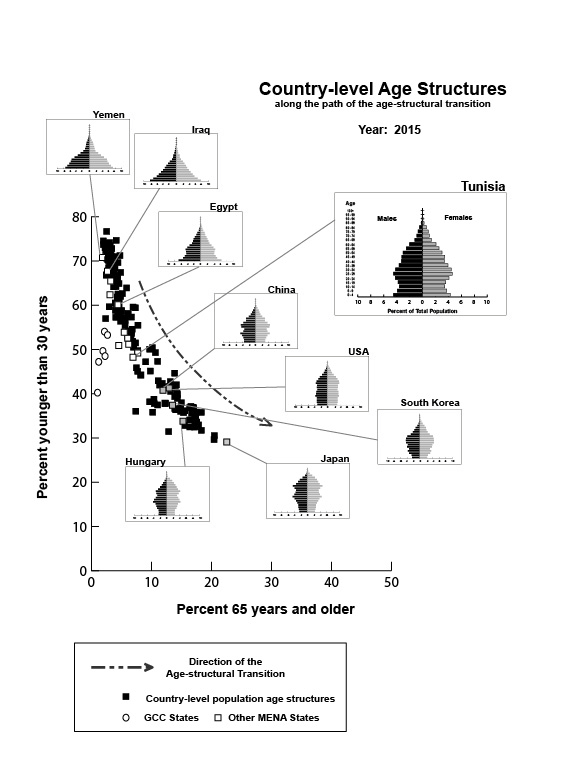

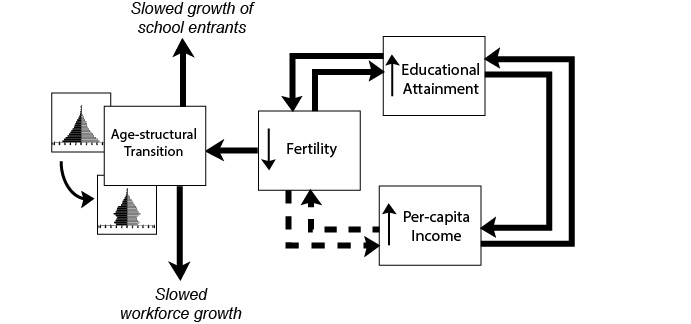

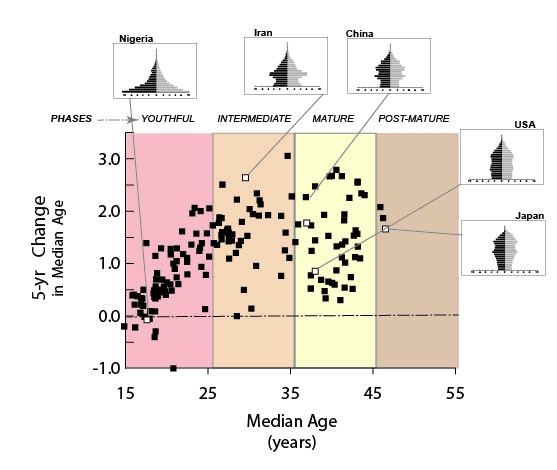

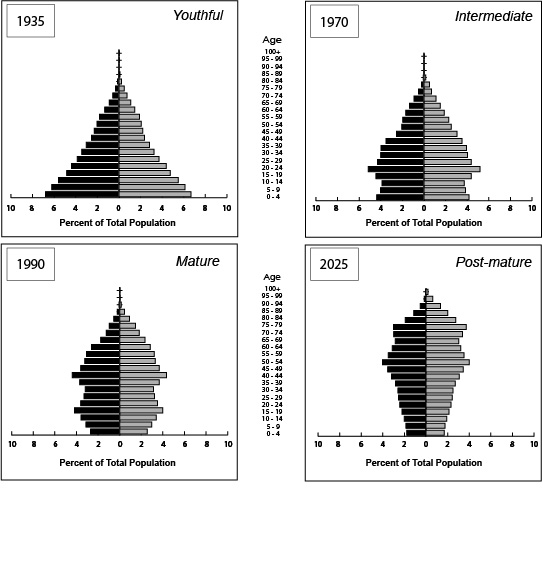

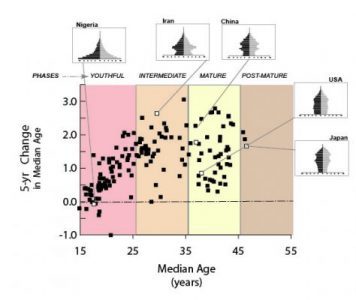

Rather than focusing on explanatory narratives and causality, the Age-structural Theory of State Behavior is concerned with generating “timed expectations.” At the core of this theory lies the age-structural transition—the continuous path of cohort re-configuration that leads from a youthful population, to one numerically dominated by middle-age adults and seniors. Age-structural Theory’s most tested models and functional forms are built upon this fundamental demographic process.

The body of Age-structural Theory is growing. At the leading edge of age-structural research is an expanding set of newly generated models, each reflecting a hypothesized relationship between the known position of states in this transition, and their corresponding likelihood of being observed in a specific political, social, or economic condition. In time, some of these hypothetical models will undoubtedly become more deeply woven into Age-structural Theory—but only if successful forecasts and other out-of-sample tests show them worthy of greater certainty, and if they are found analytically useful or create “new insights” into the relationships that they portray.

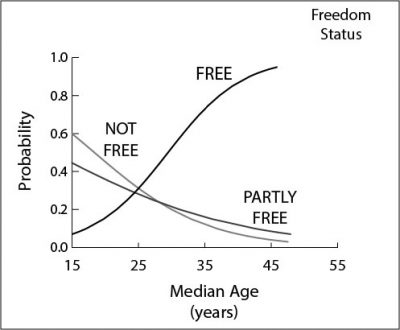

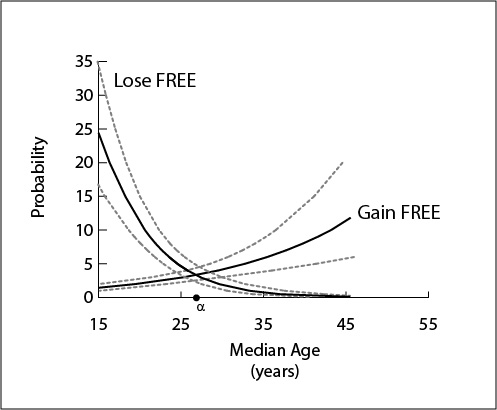

Forecasting is integral to Age-structural Theory. To investigate the future, age-structural models are simply re-positioned one or two decades into the future—into a demographic future already described in detail by the UN Population Division’s (UNPD’s) series of demographic projections (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division [UNPD], 2015). Since age-structural models were first generated in 2008, this method has yielded a string of successful forecasts, discerning a “window of time” for future events and oncoming conditions that regional and country experts missed or thought were improbable. Moreover, several of the early conclusions of age-structural models—that states with youthful populations are vulnerable to political violence and experience difficult political and social environments for achieving and maintaining democracy—are increasingly accepted as fact by many foreign affairs policymakers.