See the Population Reference Bureau’s excellent video explaining the “Four Dividends” that countries generally attain following fertility decline as they pass through the demographic window. These four dividends are: (1) child survival, (2) educational attainment, (3) per-capita income, and (4) political stability (measured by 10-year risk of intra-state conflict).

See the Population Reference Bureau’s excellent video explaining the “Four Dividends” that countries generally attain following fertility decline as they pass through the demographic window. These four dividends are: (1) child survival, (2) educational attainment, (3) per-capita income, and (4) political stability (measured by 10-year risk of intra-state conflict).

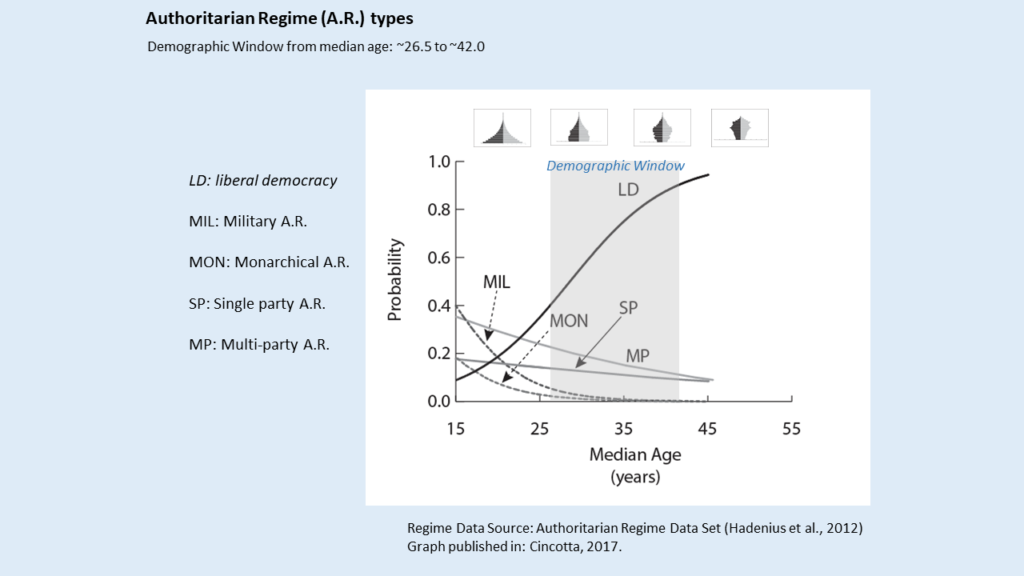

Here are links to obtain the IUSSP Conference paper (authored by Elizabeth Madsen and me) that describes the timing of these changes, in terms of the movement of countries through the age-structural transition. A background paper on the Age-structural Theory of State Behavior is published in the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Some of this information is published in a short essay on the “Eight Rules of Political Demography“, on the New Security Beat.

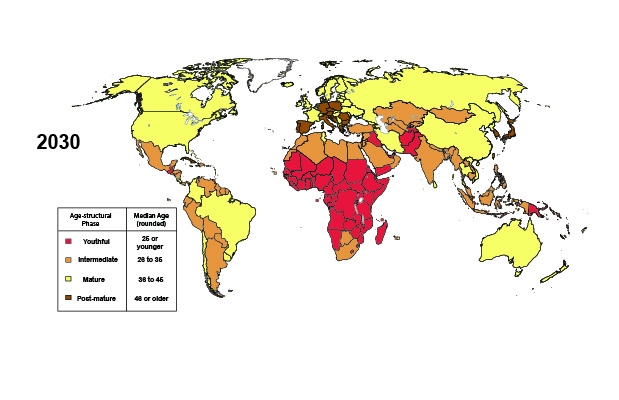

Over the past 25 years, economic and political demographers have focused on documenting the improvements in state capacity and political stability that have been realized in the wake of fertility declines in much of East Asia, Latin America, and most recently in the Maghreb of North Africa (Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria). Nonetheless, foreign affairs, defense and intelligence analysts still seem confused over when and where this demographic dividend should occur—and whether the youthful, low-income states of Sub-Saharan Africa are due to experience the dividend’s economically favorable age structures anytime soon. Because two very different development narratives vie for these analysts’ attention, their confusion is not that surprising.

Over the past 25 years, economic and political demographers have focused on documenting the improvements in state capacity and political stability that have been realized in the wake of fertility declines in much of East Asia, Latin America, and most recently in the Maghreb of North Africa (Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria). Nonetheless, foreign affairs, defense and intelligence analysts still seem confused over when and where this demographic dividend should occur—and whether the youthful, low-income states of Sub-Saharan Africa are due to experience the dividend’s economically favorable age structures anytime soon. Because two very different development narratives vie for these analysts’ attention, their confusion is not that surprising.

Early advances in age-structural political demography were pioneered within the (U.S.) National Intelligence Council’s Long-range Analysis Unit (now called “Strategic Futures”). That work has continued through collaborations between the NIC and political demographers. Some of the NIC’s political demography products are featured in three of hte NIC’s quadrennial strategic foresight series, entitled Global Trends.

Early advances in age-structural political demography were pioneered within the (U.S.) National Intelligence Council’s Long-range Analysis Unit (now called “Strategic Futures”). That work has continued through collaborations between the NIC and political demographers. Some of the NIC’s political demography products are featured in three of hte NIC’s quadrennial strategic foresight series, entitled Global Trends.