Welcome to politicaldemography.org

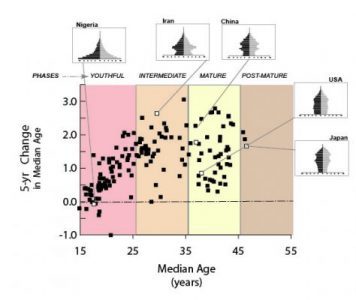

Defining the Demographic Window

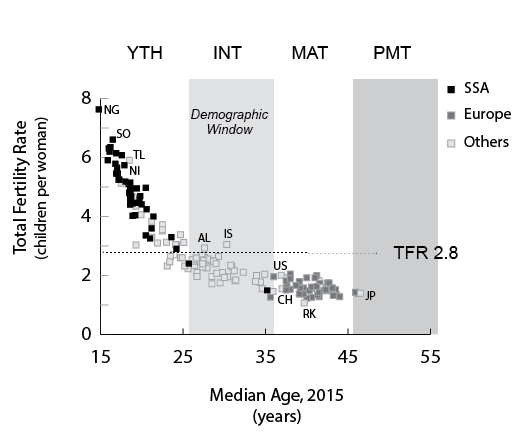

Introduced by UN demographers during the Population Division’s release of a series of long-range projections (UNPD 2004, 2, 70-73), the original intent of the demographic window was to call attention to the segment of the age-structural transition that tends to measurably favor economic development. In its original formulation, UN demographers assumed that this window occurs when both children (0 to 14 years) and seniors (65 and older)—age groups that are composed principally of dependents—are at a low ebb. However, unlike other measures of dependency, in the UNPD’s formulation, children and seniors are differentially weighted; each senior is assumed to represent twice the per-child burden on economic development. According to this method, the demographic window is deemed open when children comprise less than 30 percent of the total population, and simultaneously, seniors comprise less than 15 percent of the total population.

Despite its seemingly arbitrary rules and speculative boundaries, in practice the UNPD’s demographic window has done well identifying conditions during which states achieve the World Bank’s upper-middle income classification, a milestone in development. For example, among the World Bank’s 2018 list of upper-middle income states, all are either in the UNPD’s demographic window or have passed through it (World Bank, 2019). The remainder are either significant oil and/or mineral exporters or have a population under 5.0 million—a group that includes numerous island states with exceptional per-capita tourist revenue and/or remittances.

Coupled with the UNPD’s demographic estimates and projections, the analytical usefulness of this simply defined window is obvious. To make the concept compatible with the conventions of age-structural modeling, Cincotta (2017) employed the UNPD (2004) metric to estimate the median ages of its assumed boundaries. From a sample comprising the 40 states that had entered that window since 1950 (excluding states with greater than 15 percent of GDP in oil or mineral rents). On this basis, the UNPD’s demographic window generally began at a median age between 26 and 27 years. Among most of the sample, the window ended at a median age between 39 and 42 years.

Using the lower median age boundary, Cincotta (2017) noted that states are generally unable to enter the demographic window without declining below a total fertility rate (TFR) of 2.8 children per woman (Fig. 4). Nonetheless, among states that have sustained rapid rates of fertility decline, populations have often declined well below a TFR of 2.8 before achieving a median age of 26 years. As these states aged—as relatively large cohorts of children and adolescents were replaced by smaller cohorts—they usually crossed the window’s nominal threshold within a decade.

This

analysis noted that for most states, their trip through this demographic window

of favorable age structures is likely to be a onetime opportunity—but with

exceptions. The length of chronological time spent in the demographic window has

occasionally been extended, at least temporarily, by: (a.) a baby boom, such as

the post-war WWII rebound in fertility in the United States and in some Western

European states; (b.) an influx of youthful immigrants; (c.) sustained rapid

population growth among an ethnic minority with significantly

higher-than-replacement fertility; or (d.) fertility settling near replacement

levels, with very low child mortality.

Attachments

Israeli demography and politics: The growth of the Ultra-Orthodox

Rapid growth among the Haredi (Ultra-Orthodox) sector of Israel’s population has been a two-edged sword for Israel’s right-wing political parties. On one hand, the Haredim’s intensely youthful age structure contributes a larger cohort into the voting-age population with each successive election, yielding an increasingly larger contingent from United Torah Judaism (UJT), a voting list comprised of two Ashkenazi-Haredi parties: Degal HaTorah and Agudat Israel (See a 2013 article, published by FPRI, on the changing demographics of Israeli elections, also available on the FPRI website).

Rapid growth among the Haredi (Ultra-Orthodox) sector of Israel’s population has been a two-edged sword for Israel’s right-wing political parties. On one hand, the Haredim’s intensely youthful age structure contributes a larger cohort into the voting-age population with each successive election, yielding an increasingly larger contingent from United Torah Judaism (UJT), a voting list comprised of two Ashkenazi-Haredi parties: Degal HaTorah and Agudat Israel (See a 2013 article, published by FPRI, on the changing demographics of Israeli elections, also available on the FPRI website).On the other hand, the ever-increasing Haredi voting power and its reflection in Israel’s 120-seat Knesset chafes hard on several of the right-wing and centrist parties (as well as the Knesset’s dwindling Left) and their constituents. Like Avigdor Lieberman’s Party, Yisrael Beitenu (representing immigrants from the former-Soviet Union), these parties are adamant that Haredim young men perform service in Israel’s Defense Force–a duty that is accepted by all other Jewish Israelis (including new immigrants), as well as by many among the Druze and Circassian minorities.

The recent 2019 Knesset election has brought this problem to a head. However, it’s nothing new — “the deal” with the Haredim has been a potential sticking point for right-wing governments for the past decade. Ironically, the Haredim’s sustained high fertility rates guarantee a larger and larger share of right-wing votes, but their presence in government and insistence on special privileges (family subsidies, exemptions from military service, and control of many aspects of Jewish law) has made it increasingly difficult to form a government (see article in Al Monitor by Ben Caspit).

Guest Lecture: Florida International University

The PowerPoint slides for my guest lecture in Prof. Shlomi Dinar’s class in FIU’s Masters of Arts in Global Affairs Program are posted here. Please browse this website for more information on the age-structural theory of state behavior and visit my pages on the New Security Beat blog for short essays which employ this theory. A brief article (blog) that sums up the findings is: “The Eight Rules of Political Demography” (July 2017).

Lecture: US Army Future Studies Group

At the following links, please find the PowerPoint slides presented and the handout provided at the AFSG lecture session on March 7, 2019. Thanks for the invite, AFSG. Your questions were excellent–probably the most perceptive set I’ve ever fielded (or tried to field).

If you would like to look at some of the theory/applied studies, please cruise through the menus on this website, and read a few of the short essays on political demography (2-3 pagers) on the Wilson Center’s New Security Beat.

Attachments

Guest Lecture: GMU/Govt444

The PowerPoint slides that were presented in my lecture in Prof. Jack Goldstone’s GOVT444 class at GMU on Feb. 27, 2019 (James Buchanan Bldg., noon) are posted here. If you attended the class, thank you for your attention and questions.

If, by any chance, you would like to know more about the predictions of the age-structural theory, continue reading the posts on this site and the essays organized by the menu. In addition, see the latest posts on political demography on the New Security Beat. They’re quick reading.